“This is Panarchy, Man!”

[…more forthcoming.]

“This is Panarchy, Man!”

[…more forthcoming.]

Poem for the Right and for the Wrong

In the Spring

everything is names

and numbers

messages sent

at the same time

and the way

the most simple ‘hello’

can sound so familiar

when I’m on my porch

alone

for all of May

with the songs

about songs

saying something

about turning

my back

on a friend

and me trying to figure

who I was turning on more

after all was said

with not much done

it was only me

alone on my porch

in spite of

that white bird

that blue shirt

all of this after

the long slow thaw

and how we danced

through those months

of too-short days

there’s no such thing

as wasted time

and even though

I never did find out

if you could slow down

the clock

I don’t believe

in broken hearts anymore

not on days like this

with everything so hot

like blood in the sun

and so much living and dying

while the grass just keeps on

growing

and the clouds

look like they’re trying

to rain

I’ll just keep telling the story

of the two copperheads

that my father killed

in the woodpile on a Sunday

while the pear trees

smelled like sex

and the bees buzzed on

like it was nothing

like it was nothing

like it was nothing

under those skies

on that finally quiet day

in June

when it just didn’t matter

all that much

anymore

what I claimed to choose.

Unsculpture

Today, without ceremony,

sans sentiment

I tore down the Hand of God

(untitled)

or at least started to anyway,

I left the frame

for another day,

another afternoon.

Unremarkable,

just cleaning up

an old mess I made.

Broken glass and the rust

of a yesteryear righteousness

the chicken wire

drawing blood

the hardware cloth

the nails

in a skeleton

of rotted wood

there in the Northwest corner

of my yard

which was,

years ago,

a beautiful place

and is still a beautiful place

though in a different way,

a far more moldering way.

Today, without ceremony,

without a single photo,

I peeled away the splintering waves

pushed the boat from where it sailed

atop the frame

and felt pleased

when it shuddered and cracked

upon hitting the ground

tearing a limb from the maple

as it fell,

in a great feat

reversed.

I pushed down

what I had once pushed up

and the children were just as delighted

to see it destroyed,

as they were when I raised it from the ground,

over my head,

and pushed, pushed,

up toward the sky.

“This is fun,” my son called,

as he smashed the boat apart

there on the muddy ground,

without ceremony.

Formation Song

These raindrops,

half-hearted until I really listened,

sound out a serious rhythm

a march to war,

a grand rally,

a big game

something more important than anything

that this day

just beginning – damp and lazy,

would seem to have in its plans

But, on the old metal sawhorse

whose only work now

is to patiently hold back the Calycanthus

and to slowly rust

in the corner of the yard

a movement is mounting

a syncopation found

in the hapless fall of water

being pulled back into the earth

doing the only thing it can do

when it finds the edge of the roof

which is to dumbly drop

with no knowing and no intent

And, oh, surprise

it becomes

a battle hymn

steady and certain

for this morning that is full

of quiet, whole-hearted falls

and almost unnoticeable journeys

back to where we belong.

An Imperfect Sonnet for a Dying Mother

How can I tell you, my dying mother

that you will turn to a bright comet soul

upon death, when the body becomes other

a wish to stay is the most futile goal

Your gaze to the edge of the field is long

hands clasped tightly, holding luminous ropes

“What?” she says, “I will miss life. Is that wrong?”

the mortal’s love spans all lands of false hopes

Yet, I am certain that with final breath

you will see, your eyes untethered at last

it’s true: the dead miss nothing upon death

we all become like comets, light and fast

The falling star does not cling to the night

even unseen, it shines then dies bright

To say you are the bones of your old hands

metacarpals, nails bent, a dying liver

the blood and substance of ancestral lands

in veins that cross flesh branched as a river

to call yourself by the knots of your spine

looking in the mirror at the face you know

not catching reflections, simple lines

the arrow fallen away from the bow

You are convinced that the name they gave you

bundled mass of cells and new beating heart

is somehow yours eternal and most true

from which you can and never will part

Your real name is a whisper on warm wind

The Scientist’s Lobotomy

Did you look inside her

at that place

where you imagined

all those demons, that disease?

Was she split open

like a shell

for its soft fruit

to be examined

by the stainless tines

of science?

What did you find, in that shimmering inside?

Was it not so dark as you thought it might be?

Did you see, there in the folds, the pits that you pictured?

Did you find

what you expected

empires of rot and lesion?

Did you swim

in the swamps

tucked into the coasts between

this region and that region,

get lost in the tangles

like cities on a roadmap?

Or was it softer, smoother…perfect?

Did the gentle pink edge remind you of a shell

that you once picked up from the shallows of the ocean?

Did the salt on your lips taste like waves?

There were patterns in the sand and you traced them

as mountains.

You saw the pools, your eyes reflected against the sky reflected …and you knew the truth.

You found it in that shell that held the sunset.

That soft slick pink and bruise

of grey and blue

that felt, to you,

soft like your mother

could never be.

For a moment, the whole world was there

and your finger felt

the sound inside

like music.

It’s so easy to forget

that you wanted to live

inside that place

where the ocean roared

against your ear

for you alone to hear.

When you looked inside

did you see

the landscape of her memory?

Was the universe in there?

Did it look like sand?

…or just a small segment

of tissue asleep

that you carved out

and placed on a scale,

as though this matter

could be weighed?

Was it barely alive at all?

Tell me, what was the smell of her,

in that deep

dark opening

that you made?

Did you find, tucked into a crenellated warmth,

the place where her voice

was born?

You never heard it.

She never spoke.

You never listened?

You’ve forgotten

which came first and what it was

that you were looking for

in the first place

in that space

behind her closed eyes.

Do you see that, even sleeping, her mouth looks like a bow?

You have no way of knowing

that as a child

she sang the same song

over and over again

because it made her happy,

made her heart lift up to the clouds,

spirits spinning melody.

Tell me, when you pulled

the two halves apart

did they make

any noise at all?

Tell me, what did you see inside?

Did you find God?

…or did God find you?

F.R. Rhyne (2019-2020)

1 – 8, Speech

roll your tongue, pushing

pulling air into your lungs

spitting out the truth

It sounds like, “Ahem,”

“Hmmm,” “Uhhhhh,” “Ungh,” “Ach,” “I…don’t know…”

how to speak it clear…

a quiet phrasing

sun scent of warming grasses

softer expression

thin reed whistle sound

pitched like the tilt of a bird’s wing

cutting bright air clean

comes as a stumble

breaking wavelet memory

grit of sand, breadfruit

warmly sticky hands

fatigue of dirt road laughing

symphony at night

sour sweet brother breath

heavy sigh as puppies sleep

adults speaking low

almost separate

a photograph held lightly

“Was this us? Really?”

9 – 12, Before Time

…there are no word-sounds

for the beginning movements,

before anything

What was there? Expanse?

Just a void-full vacuum space?

An empty socket?

There can be no wind,

if nothing moves a muscle.

No wind, no muscles.

so conspicuous,

the absence of everything

we might call ‘alive’

13 – 17, Melding

arrangements were made

atom configurations

created the spark

Ain’t got a name, no

or a mind like our new minds

no sense of itself

no imagined time

or knowledge of space beyond

nothing but knowing

Knowing not like us,

but, moving without effort

without intention

The sweetest pulling

elemental attraction

bonds beyond breaking

18, Initial Questions

Was there a whisper,

a murmuring in the dark?

Did the first cells sigh?

19 – 23, Utterances

beautiful, we were

in all the ways we have been

alive and dying

The snow and ice

the fires and beasts, new life

not knowing what comes

oh, to remember

that the world was here before

we discovered names

…all so long ago,

there is no one who can tell,

can’t speak that story.

silent origins

are not soundless, listen here:

speech without talking

25 – 28, Without Knowing

bromeliads grew

and the lizards sprouted wings

it took a good while

before winding clocks

or any imagining

of long nighttime hours

slow living and death

just as daily as it is now

without knowing time

there was no distance

no measurement of the miles

nothing had a name

29, Truth

the land was nameless

there was no way to say ‘home’

no one to say ‘home’

30 – 33, Innation

all creatures know, tho’…

creation lessons taught them

where they can survive

all things born knowing

what they crave and what they fear

DNA knowledge

To run, to jump, dig

to eat grubs, seeds, fish, algae

to keep on living

Pituitary

endocrine and thyroid gland

signaling us: Grow.

34 – 35, 4 Ws

We learn as we go

the sourness and sickness,

the sweetness and warmth

we thrive or falter

depending on when and where

who, what we are born

36, Truth (2)

for some of us here

life is a slow-blinking eye

over and done, gone

37 – 40, Instinct

the first words were grunts

howls, songs sung without singing

the scream of murder

storms were almighty

new hominids had no gods

death-fear was instinct

the striving of life

required no will at all

it was natural

To seek out food, hunt

to gather, drink water from leaves

these were not choices

41, Truth(3)

oceans did not choose

the rhythm of tidal flow

rain falls without choice

42 – 46, Anthro

afarensis, comprende?

Australopithecus, yo?

Old Lucy no se

it became a job

to dig up hundreds of bones

study the fragments

unearth the sacred

Use the most delicate brush

remove dirt from teeth

Lay out the bodies

rib cage, femur, mandible

marvel at the skulls

Ethiopia

Tanzania, Olduvai

footprints left in ash

47 – 50, Naming

our ancestors died

howling in the flaming heat

without knowing death

Homo habilis

Long prior to the Maasai

Place of wild sisal

The Great Rift Valley

one million years ago, man

Kariandusi

These are made up names

for places we claim to know

as ours to lay claim

51 – 54, History

Thick walls enclosing

the city-town of Jericho…

why did they need walls?

Catal Huyuk held

spaces for worship, women

made of stone and clay

Organized villages

created special labors

jobs and roles, talents

Tasks took on value

products emerged in surplus

trade began, tribes fought

55 – 57, In Modern Rendition

How does this show up

thousands of years later?

Colonial turf wars

even kids know it

colors become codified

Street sign boundaries

Elder mothers mourn

keep their own pistols loaded

Please God, watch over us.

58 – 61, of Weaponry

The earliest tools

were not made of rock and sharp bone

clawed hands were weapons

Closing into fists

strong, rough like worn-out leather

Dirt under broken nail

Never enough food

Had to learn to kill a deer

Satisfy hunger

The thrill of the hunt

predatory lust writ deep

makes human hearts beat

62 – 66, Where We Came…

go to the river

each day, every morning

wash away the blood

tell us the story

of the animals’ escape

speak in native tongue

myths of creation

shape the world as we see it

center us or them

have to be careful

of the tales we tell children

about who they are

Where did we come from?

Not our bodies, our cells, bones –

the naming of us.

67 – 70, From

Judaculla’s rock

sits speaking in the forest

speaks silent under trees.

Spelling a story

lines cut into the hard rock

for the future ones

Maps are like stories,

stories are like maps, like guides

telling us the way

Children taking turns

wander through woods far from home

name them “good” or “bad”

71 – 78, Prior

There were buffalo

clear to the ocean, huge herds

land belonged to them

This place was their home

the fields and the valley grass

their bones are still here

The water flowing

here, right on through the mountains

thousands of years old

mountains were jagged

Earth slamming into itself

rocks jutting from collisions

Broken pottery

found in the soil below banks

worn smooth at the edges

the flow of the streams

in places now dry, barren

written as ridges

From above, the lines

look just like your fingerprints

swirled sand beaches

Before we could fly

everything was smaller

and yet still so vast

81 – 88, Forging

roots grow persistent

somehow breaking through hard stone

making small pathways

In the night, rocks fall

land heavy and stay forever

or til they erode…

it’s not a secret:

there is no forever here

it’s easy to see.

Yawn, oh great cloud break

not witnessed in the pre-dawn

opening above

The breath of owl song

a thread through trees, pushing soft

making sound-cut spaces

Tilt of the orbit

positions a planet near

closer to the moon

The woman pauses

never noticed that before

Looking up, surprised

There are slim chances

brief windows, prime conditions

sap rise, season shift

89 – 95, Forests

No words for the sound

capillaries opening

eyes dilating wide

Tremble of vein stretch

cellulose walls forming up

to become an oak

Entire empires thrive

tucked in around the root web

pulsing in dark soil

scientists can hear

by way of lines on paper

amplification

voices from the trees

the subaudible gasping

bite of the chainsaw

how to amplify

millions of hearts beating fast

terrified in flight

pass the mic over

colonies of insects scurry

carry out big plans

96 – 100, Archae

Skilled human being

2.5 million years ago

Homo habilis

it was crucible

the birth place, cradling us

civilization

Land was colored gold

and gods lived everywhere

in everything

winds and fires speak

tell what those who came before

wish us to know, hear

secrets conjured up

feet hit the ground, dust rising

bones shake, rattle, roll

101 – 107, Habit

be invisible

walk without touching the ground

do not make a sound

cover the smell up

with crushed leaves, sharp scent, thick mud

leave no tracks, no trace

Hold the arrow lightly

let it be a part of you

send the point flying

Homo sapiens

the thinking human being

moved outward, naming

Paleolithic

stone tools to cut, smash, break

all with bloody hands

When the ice came

there was no lamenting cold

no questioning death

We didn’t see it

had no way to predict rain

unstoppable floods

108 – 110, Innovate

Speech was simple code

utterance and gesturing

pitch to make meaning

sequences set firm

names for flames and lions, sky

sounds for who we are

in all four corners,

seeds were sown, barley millet

rice wheat lentils corn

How did it happen?

That we suddenly knew how

to grow food to eat?

Burgeoning, winning

the thrust of diving hawk flight

cutting through the fields

111 – 115, Alchemy

our life histories

begin with the history

of all before us

They carried whispers

small stirrings that make breezes

from the prior ages

They made the world new

from mud, stars, from their own blood

they breathed life into…

they still exist, gods

even if we don’t know their stories

Don’t see them in wind

we were directed

our organs pulsed with humors

blood was once magic

116 – 121, Numinosity

schematics and maps

drew a firmament dome, hands

in the human form

world in our image

not in God’s image, in ours

at least some of ours…

Early ones knew well

that man was imperfect, crude

not like the great beasts

The ones with horns

with wings and fins, lionine

crafting the storms

There were spirit forms

and powerful dark beings

exist, still unseen

Holy books are full

cloudforms speaking, fire and blight

all the miracles

122 – 127, Composite

Look closely, breathe in

count the layers in silence

stratification

When I look at you

salt stings my eyes, I tremble

welcomed home again.

how can the clouds hold

water in the shapes of bears

briefly showing themselves?

birth of rare fever

blooming jewel of Africa

blood-colored flowers

Craving to eat stones

let them rest under the tongue

to spit or swallow

shines like dew, slug trails

dash of stars, the Milky Way‘s

constituent parts

128 – 134, -onyms

Timucuans lived

had numerous settlements

all along rivers

Names for homeplaces

never knew them to forget

“ancient history”

Never such a thing

as a “Timucuan” tribe

Spanish mispronounced

Exonyms misheard

Double mistakes in hearing

become the name known

Letters we use say

nothing of the sounds spoken

such crude translations

Two hundred thousand

more than all that died in wars

in one hundred years

that was just one tribe

one people among many

whose names we don’t know

135 – 139, Panther

in the night, she walks

slow and careful, listening

for raccoons, possums

eyes glint gold in dark

thick insect symphony sounds

rhythms for hunting

wild boars aren’t careful

they get busy, distracted

rooting, face in dirt

It’s almost easy

to run into the pack, claws out

and grab what you can

scattering screaming

everything exploding

in movement and fear

140 – 143, Sensing

In the forest shade

a tiny life moves fast, light

under leaves cool, damp.

Talon on the branch

sharper than made by machines,

perfect feathering.

The wave of a pulse,

and the night quivers alive

with unseen currents.

I’m far from the owl.

There’s too much to do everyday,

to sense a heartbeat.

144 – 148, 1984

My great grandmother

Hands like crepe baby birds

She was a racist

I remember this

at intervals, dawn

and right before sleep

Who and where and what

we are, the people, places

that gave birth to us

It all rushes in

adrenaline, cortisol

spitting out the words

refusal to go

Unsegregated swimming

1984

149 – 158, Combat

Their jawlines were smooth

tho’ hands were rough from working

holding rusted guns

Men, closed offices

drawing lines, cartography

X marks the target

my brother, your kin

became numbers, troops deployed

to die for ideas

Sleep was a joke, son

No rest for the weary there

under hellfire rain

Dream never again

no softness, no golden fields

just red explosions

it’s a trick, you see

to turn men into machines

to command their will

soil holds vibrations

sings rusted earth elegies

lay your head down, son

a monarch catches

air currents undetected

becomes transparent

walls crumble in wind

ultraviolet light dissolves

clay and stone, slowly

reports ring out, CRACK

doesn’t it split your head wide?

cities up in smoke

159 – 165, Multiplicities

In the midst of war

starvation, emergency

grasses softly blow

In dark, lives away

Gunshots ring out across town

the fire burns warm

smart submarines rest

in channels dredged from the deep

bombs in their bellies

show security badge

drive through armed gate, go slowly

everything is filmed

Trains come, broad daylight

take new spur line to the north

carrying supplies

Lockheed Martin watches

Trident Training officers

show the simulated launch

take a deep breath now

all your friends are doing it

step onto the rails

166 – 172, Entrope

You spend days waiting

looking for the envelope

but don’t want to know

You can’t get away

from news on every screen

garish smiling faces

“This isn’t real! No!”

You want to shake their shoulders

“Wake up! It’s not real!”

It feels like ice, cold

hollow like a dying tree

how real it all is

dailyness of days

the whirlwind blur not seeing

but, moving forward

Sometimes the movements

are small, stuck tight round and round

some motion skitters

There are tangles, traps

vines of kudzu, stay busy

forever growing

173 – 180, Edu

fog creeps at dew point

Early morning siren sounds

distorted, screech owls

why is the moon located

in the wrong part of the sky

easternly crescent

secrets do not lie

in obsidian spaces

between the trees

‘Cept what do we have

a light sweeping ‘round bushes

crackling footsteps

people live in woods

sleep under tarps with wet shoes

right by middle schools

there is chain link fence

and so i feel safe, ashamed,

fearing poverty

That is my secret.

Nature doesn’t keep secrets

people keep secrets

Even to ourselves

we hide the truth, who we are,

what we learn in school

181 – 187, Peri-

cadence of footfalls

dry brush of cardboard boxes

thudding gravity

rubber wheels cheapen

nuance of selecting meat

unsanitized hands

To walk like a whisper

imagine air as body

and watch where you step

you can be soundless

almost anyway – quiet

quieter than most

unspool the wires

use the hammer to break glass

open up the line, please

She felt it, knew it

Somewhere over the mountain tops

where Chance is slow born

Full crowning takes years

and it’s easy to forget

we are in birth-time

188, (…)

body as air, rise

don’t try to beat gravity

it doesn’t exist

189 – 192, Micro/Macro

Middle of the night

hands find each other

simple human ways

The mother holds child

walks down the dirt road, pointing

there is goldenrod

They don’t stop walking

to look closer at the blooming

four kinds of bees feed

We see the whole scene

offer up broad brush coding

details become blurred

193 – 198, Coverings

We learned to weave wool

spin silk from mulberry trees

invented clothing

Polyester viscose blend

in polymers mixed to make

color of rainbows

Cover yourself, girl!

Out here nekkid in the yard –

what you thinkin’, child?

The door can close, lock

sheets smell like sunshine

or something like that

Sunshine has no smell

the scent you call sunshine fresh

chemical odor

Sunshine fresh means clean

clean means decent, and decent –

who knows what that means?

199 – 203, Carryings

Late model sedan

riding up and down the road

looking for ladies

“Need a ride, honey?”

window rolls down slow

man leans over, grins

not riding the bus

they talk at the bus stop

smoking cigarettes

Don’t talk about them,

children with names like Justice,

names like Hope and Faith

They don’t exist here

man smiling midnight, “Get in…”

opens the car door

204, Carryings(2)

they sleep still knowing

the sound of their mothers’ voices

even in dreaming

205 – 211, Relations

Ms. Social Worker

comes without calling, knocks loud

we know what it means

learned to be ready

keep the floors cleaned with Pine Sol

quick, go change the baby

Mama’s hands shake now

clatter the dishes, nervous

moving like a squirrel

they took my brother

didn’t seem to care nothin’

‘bout his crying out

He reached back to us

straining against the holding

arms straight out, grasping

was late afternoon

with the sun gold orange through pines

light, a good feeling

Officer knew us,

played football back in highschool

Mama was pretty.

212 – 214, Enter

we were all there then

my brother playing with me

in the yard, dirty

We were throwing sticks

that landed to make dust rise

dog started barking

Fence gate latch clanking

world coming in, wearing pumps

carrying clipboards

215, Yardwork

You pull the grass rough

grimace and claw, rip, tear, pop

rhizomal network

216 – 222, Sowing

To plant nasturtium

bury the seeds deep to wait

away from all light

Soak them in water

if you want to play like God

mimic the spring rain

Notice, important

the way the hulls look like brains,

gonads, ovaries

You don’t know just yet

what color the blooms will be

only that they will come

at least you hope so

pushing finger, tunneling

making birth canals

A cluster, no rows

the edge of the fence, near gate

a constellation

stretch of sunny days

unfurl like sweet promises

of orange, maybe red

223 – 228, Inside

The heft of the door,

hard seats, a screen of faces.

Print the yellow pass.

Go up, air is warm…

stuffy indoors, fluorescent…

bang, metallic sound.

Looks in people’s eyes…

speech, smile, vocal timbre…words

like a preacher says.

“Then, dude, 45…”

*hand held like a loaded gun*

“Can’t say shit ‘bout it.”

“You leave a person…”

“Alone like that, after that…”

“Man, it is not good.”

Everyone is a child

When they speak of unfairness,

the anger of all.

229 – 237, Context

Automatic doors

smell of plastic petroleum

home goods product lines

box architecture

all right angles, empty space

mimics containers

“Fill ‘er up?” “Yes, sir.”

this product is known to cause

cancer, explosions

discharge static

before fueling, touch something

electricity

hovers and buzzes

tingling, lurch, bundle and build

a haze of lightning

tiny bolts surround

gather electrons, lose them

a frenzy dance

they say the earth hums

emits constant noise unheard

makes me want to cry

Stand in the center

city swirls roaring around

great din of commerce

rises like vapor

wave crossing wave, tangling

webs shudder on lines

229 – 235, Famine Lands

They named the disease

after the first child hunger

never enough milk

The river banks steam

swarming with flies, no water

the bodies of fish

Places where grass will grow

someday for a moment, two

a generation

There is no food here

There is nothing to eat here

We are starving here

Low wail across plains

for the sons and the daughters

the kin taken far

Taken for the tusks

Taken for the strength of backs

the cords of muscle

In the world they made

Every thing has a price

despite sacred life

236 – 245, Processions

Sovereign beings all

Every creature that lives

that has ever lived

Encased in plastic

perspectives of worth

mutable and made cheap

How can we forget

The soil itself is old bones

of trees, men, and birds?

no matter trying

we cannot manufacture

water with machines

So, wring your hands, sir

Under the table, listen

there is no way out

Take the direction

opposite to the road home

walk into the dark

…day before you left

did you kneel on the ground there?

Touch the dirt and weep?

“Don’t go!” I cry out,

“Stay where you are, stay at home!”

“…you will die here, too.”

The desert lands wait

for your footsteps

migration rhythms

Desperate parade

Stooped figures travel at night

Milky Way watching

246 – 250, Deals

The starched napkins lay

Crumpled doves dinner

Plucked quick by brown hands

On the southeast side

there is no light of day shining

through the small windows

The briefing took place

in a locked room, underground

monitors record

The world will never

be the same again, any day

any second passing

There are small stirrings

noticing the child’s eyes flash

saying: “You are bad.”

251 – 255, Flee

The cities grow, sprawl

Patterning metastasis

we cannot control

Men, names like punches

that you won’t ever know, speak

holler from corners

The wives and children

huddle in rooms warm, fetid

waiting for the word

Go, go now, time comes

Mother’s blue bowl broke, oh well

one of many things lost

In the mix with bones

of trees, men, and birds, find

small fragments of glass

256 – 262, Transition

Chemicals derived

Taxus brevifolia

Kill cells good and bad

bone marrow suffers

stops making blood, hair falls out

the Pacific Yew.

My father cries now

Talks about morphine, hospice

what will happen next.

My mother’s hands, birds

resting quiet and folded

at peace in her lap

“Please come tomorrow,”

“Come whenever you can,”

“Please visit with me.”

“I’ll miss you too much,”

she says this by the flowers,

blooming brief, brightly.

How can I help her

to know and to deep-believe:

the dead miss nothing?

263 – 272, Transition(2)

The end of day comes

with my mother looking far

down the field, away

Father talked to owls

Calling soft the other night

now I hear them, too

dying has a gaze

all it’s own, mortality

written in the eyes

Oval loops in dark

running fast to feel Alive

before the sunrise

The curve of the track

Catches footstep sounds, echoes

Following faintly

I saw this morning

a bright star beside the moon

never seen before

Remember the night

at the mouth of the canyon?

The galaxy edge?

We could only see

if we didn’t try too hard,

only with soft eyes

My second born child

asked me to watch the sunrise

Of course I said: “yes.”

We saw a raven

flying low, everything

suddenly golden

273 – 279, Evolute

when industry boomed,

were birds scared of factories?

smoke and noise, machines

we watched moths turn dark

to hide in soot-covered trees

why are we surprised?

Evolution day

every moment we change

die and born again

Wise apoptosis

billions dying all the time

learning from what was

slow down, speed up, flinch

the smell of cherry blossoms,

laboratories

Atlanta, Georgia:

mice were afraid of flowers

remember the shock

Fear imprints with ease

more than love, more than comfort

Cortisol teaches

280 – 289, Old Boys

Put on your holsters

you old boys, with wagging tongues

and secret meetings…

Swallow the bullets

you’ve been saving up for us

in the name of Father

The lead sits heavy

in your soft pink gut-belly

feels heavy like fear

Hear the sound they make,

breaking the water’s surface,

setting old ghosts free?

Don’t you burn no cross,

don’t you burn no church ‘round here.

I know who you are.

I came from you, man.

Your voice sounds like home,

the place that I left.

No white robe can hide

the truth of who you are now –

scared and pink, confused.

Dirty hands, salt earth

caught under your fingernails

the bone, the marrow

Heft that anchor weight,

the blood-swollen decks creaking

with the roll of waves.

Speak your daddy’s name.

Your great great grand? Say it, too.

Ask them to tell you.

290 – 298, Stupid ?’s

Atlanta, Georgia:

When a white woman passes

Men learned to look down

No need to say why,

they were bowing their heads, pray

to Emmett Till’s ghost

You want to know why?

Smart as all you people are?

Asking is insult.

It doesn’t take brains

to notice people dying

in the streets, shot down

Do you not see it?

This whole motherf*ckin’ place

built by slave labor

Wall Street worried now,

‘bout the collapse of what was

never theirs to own

energy it took

to build this country, this wealth

rape economy

glib motherf*ckers

eating their f*cking lunches

hands bloody as hell

How dare you ask why.

Incredulous. Idiots.

You really don’t know.

299 – 306, Multiplicities(2)

Lives no longer live.

Old cotton gathering dust.

The space breathes in, out.

A declaration:

“Anxiety opposite

of humility.”

dancing the slow dance,

the steady turning of Earth.

“Oh, how she lights up!”

A blur of grasses

Gives way to edge, the township

fences along roads

The world seemed insane,

but it didn’t bother me

more than a quiver.

Flash of moving screen,

brief and inspecific weight

shifting in my core.

Before the sun came up

the elder woman walked slow,

a moving treadmill.

Watching the reel play

silent, muted, on flat screen,

no certain futures.

307 – 311, Stagger

distance between worlds

one person to another

a moment passing

we adjust quickly

our adaptability

new realities

We forget the names

creatures extinct, this century

whole histories lost

rushing toward the new

we tear down what was sacred

spewing exhaust fumes

left alone too long

it all goes back to the wild

strong instincts of plants

312 – 321, No Frontera

All weariness gone

watch under ponderosa

hummingbird cloud sky

desert night is long

Factory Butte lit by moon

illuminated like day

equisetum lashes

legs scratched and burning red raw

prehistoric plants

how human to see

fire in the sky as God’s work,

something like magic

small rocks hold color

like the big hills and mesas

similarity

dead truck container

virtual reality

Arizona road

Ravens flash black wing

a suburbanite is stunned

valley of the gods

Canyons sleep sundown

Pinyon quiet windless night

the beautiful wild

The grass catches light

shining golden afternoon

rarely seen glowing

Quiet breathes easy

here in the canyon silence

just the sighing wind

322 – 329, Dead Lands

How many days in

the millions of years it took

to make the land here?

This place was on fire

seasons burning on and on

cold in the morning

western towns cluttered

with junk we thought we needed

rusting along roads

New side of town lights

pizza storage rusting tin

desert winds blow dust

Random road messages

give hope to dreamers, gamblers

Long shot, all is true

I caught signal here

under high point juniper

to listen, hear truth

She said on the phone,

“I can’t really be myself,

in this life, my life.”

Two ravens watch cars

guarding town or the highway

or nothing at all.

330 – 337, Parking Lots

We tend toward order

the implicit pull to lines

numbers, doors, closed, *lock*.

Man, geometry

hard edges everywhere

except reflected

Things we hold onto

Stored for a possible life

we need to let go

pull back your shoulders

throw your fist in living air

you are really free

Find moments of breath

to see the shape of wind waves

carve dances in trees

The gods sleep gape-mouthed

Crawl in like a dream, settle

as a prayer-thought

They will wake with you

in the turning of the winds

the spinning of time

when widening luck

and rich configurations

clear the space ahead

338 – 346, Moves

American road

The river down below us

flows quiet like it does

The brand new of youth

gave way to just skeletons

gasoline for sale

It wouldn’t take long

for all this to be swallowed

in green light, small trees

Things lose their shine quick

traffic traffic all day long

forgetting with ease

The names of these places

They are all made up by men

real names are secrets

Wind will tell you soft

the syllables of longing

to simply move free

There are parts of us

that never die, quiet down

“Listen, don’t forget!”

The people walked here

no choice but to leave it all

for this? Really? This?!

The grass doesn’t care

what it is called by humans

Fine blades sing real names

347 -349, Singularity

So alive to me.

Branch and bough, wind-blown and still

growing steady, slow.

In mute expansion

breathing as leaves in light breeze

What else is there now?

When sirens go by

oftenloudlyovertime

the forest exists.

350 – 352, Existing

The end is nameless

as is the mute beginning

space in wind, sunlight

The heat from buildings

shimmers across busy streets

making atmosphere

it doesn’t take faith

To know the stars are still there

even if unseen

353 – 361, Momentum

none of the girls talk

about wanting a new life

they work, no questions

At night, eyes are cast

look down at your hands, count deeds

adding up the costs

clock in, clock out, work

life is a factory now

all you’ll ever know

fingers are calloused

no softness there, at the tip

knuckles swell at night

on television

there is a bright-colored life

people laughing loud

make worthless products

your life spent earning wages

fingers twisted, sore

Give away talents

so someone else can profit

that’s the way it is

you will never see

such a vivid universe

oceans blue, sky blue

your world is dull grey

under haze of smog and ash

sun a silver disk

362 – 365, Ending

We will forget them.

The ones who came before us,

those who we destroyed.

The names we gave them

never spoke to who they were.

Names don’t tell stories.

All beings lifted…

Lord, let us be un-named now.

All beings seen whole.

The only knowing

life, death, continuation

the forever earth.

Scarborough

The woman behind the front desk,

who is quick to call any man handsome,

once told me

after she’d seen a picture

(curling at the corners, becoming indefinite at the edges, in the background)

from your marathon years

or your Navy years

or some other years

before this year

of kittens and pornography

not sleeping through the night

skipped medication

self-medication

sitting alone in the dark, the early morning

out in the county

where there is hardly a sound at 3:00am

before you didn’t sleep for days

on the long trip north

to go see your mother

dance ‘round the living room

to some song she used to like

to bicker with your remaining brother

your last brother

the good son, the one who didn’t kill himself,

who stayed alive, stayed home, became impatient

and complained to you

about the mess of her eating,

the food falling out of the mouth

that sang you to sleep

before you got on the bus

before you were the far away son, the runaway son

the man who left the kittens

in these stupid mountains

that were never your home

because you wanted to tell your mother goodbye

when you thought

she would be the one

to die first. You were handsome, before all that.

To tell you her life story,

she’d crawl under that low table,

tuck into a ball,

duck walk crawl,

lay down flat-bellied

on the nubbed-out carpet

Smelling dirt and plastic,

the cold of the concrete in the floor seeps up.

She’d tell about watching

small hands fidget,

rising and falling from tabletop to chair

elbows pressed close to bodies

and feet hooked ‘round the legs of chairs,

scuffing, rolling toes.

Air too warm,

like sleeping breath.

Thick buzz of sound and light,

making tired,

voices, thin windows in the corner

green grass between buildings,

hard look of brick.

Nothing at home was made of brick

except the bottom part

of her great-grandmother’s house

and old fallen chimneys out in the woods,

from people that’d been there before,

after the other people who had been there.

You felt quiet

still and cool in the yellow white light

the cinder block room

eyelashes curled up silky and black

butterfly mouth, proboscis

a word you’d never heard, did not know

skin, the river bank

right hand was resting on the edge of the table

thumb feeling out the line from top to side,

the formic seam

some pages flat and silent

Adult voice

droning layer in the air

heavy over the room of round tables

Your hand drops to the edge of the chair,

under the table, into the shade

feels along the hard yellow

lean the body forward, hold to the silvery leg

She felt a crawling toward,

nervous animal,

hand under the table

only a foot away

surprising how easy it is

for hands to find one another,

familiar clasp, palm across palm

fingerprints like the river we grew up on

hot and dry, the dock railing in the summer sun

There’s no way she could tell,

and no reason she’d need to,

because you felt it, too

the cold of that grasp,

adult hand like air conditioning

smooth and bloodless

the pulling the warm creatures curled together

up into the bright of the room above the table

lifting the holding hands like some dead thing,

some sad thing.

“You will not,”

voice from behind, from above,

before they knew what was happening,

hands still clasped together,

dumb and silent in the air,

because what can a child’s fingers speak,

“hold hands with,”

wrists encircled,

a swift outward pull, uncoupling the grasp

breaking the hold

set the hands firmly onto the table,

issue the declaration

that tells the story of who they are,

“little white girls.”

To tell you her life story,

she’d have to crawl down on the floor,

hands and knees,

and tell you that she knows:

This isn’t her life story,

in the way that it is yours.

Old Boy, swallow your bullets

let the lead

sit in your belly

that weight like an anchor

holding a Bloated wood hull

Blood-swollen decks

right offshore, right offshore

You old boys, with wagging tongues

and shotgun shells

your backroom meetings

dirty hands, the salt of the earth

all its bones, all its marrow

caught under your nails

You old boys, don’t think that I don’t know you.

I came from you.

Old Boy, don’t you burn no churches ’round here

don’t you burn no crosses

because I know who you are.

I came from you.

All the sheets in the world can’t hide the truth

of who you are.

I can see right through them.

You’re pink and soft, trembling and damp.

You’re scared, Old Boy.

You’ve always been scared.

So, you just swallow those bullets that you’ve been saving up

in the name of your own daddy

in the name of your own greatgrands

and the slow death

of the world they taught you to believe in

You just let that lead sit there in your belly

like the weight of everything you came from.

or, better yet, throw those bullets out into the river,

and listen to the sound they make

when they break the surface

setting all those old ghosts free.

In the thick ribbon of sucking tires

The shimmer of the earth ground to twinkling dust gathered at the barrier seams as snow that swirls and hushes at the edge of the roar I travel in insulated and absurd under grinning proclamations of injury and payout, promises of justice and redemption spelled in bright red, bright yellow As I travel to retrieve you by means of this road, which is not the only road, but is the quickest, despite my slowing, despite the impossibility of passage that mounts at the cloverleaf, the junction, the joining of major channels all witnessed blithely by the Waffle House that has turned into a We Buy Gold, announcing in familiar block black letters the eventual way of everything around here.

And you are landing as I stall under the reluctant sunrise that slow sighs a dull orange across the stunned oaks that pull to the forest that surely the fibers of their cambium remember as sweet water and blessed breeze the air pulling at stiff leaf and nimble green branch, up, up, into the air

As you come down, as stunned as the oak into all this mess from the bliss of empty spaces and open sky, only to see me, to come home to me and I know, in the early morning that I have near forgotten, that to have a home to return to makes the departure possible, defines, in fact, the adventure as something other than just a sad wandering away from something that does not love you, that cannot love anything, not even the gold it buys with the payout, even the triumph of the super highway, even the majesty of the unseen oaks sliding by as I get a little closer to welcoming you home.

I drove two thousand miles

to find you in a parking lot,

to walk over slickrock with you,

to eat eggs

in the places where people used to live,

but don’t live now,

those canyons filled with echoes

I didn’t know

that I was supposed to meet another man

in another parking lot

while you fumbled for directions

with weak data.

Maybe I was?

Maybe I wasn’t.

In any event,

there were 9 ravens in the sky,

and a white bird like a hawk,

maybe a golden eagle,

like we saw a couple of days later,

in that Cortez parking lot,

drinking melted ice cream,

that warm day when the dog died,

back home,

right before my father’s birthday.

I held the drunk old man’s hand

listened to him talk about:

how long her hair was, how he wakes in the night and cries, his daughter that is off to war in Afghanistan, how he used to jump out of planes in the dark, was just a body falling, before he came home to be a Navajo again, before he ever knew that he would wake up at night thinking about the war, would drink himself to sleep for years…

I think we said a prayer together?

I gave him my phone number,

and he gave me a rock.

He never called.

At least I don’t think he did?

I don’t know.

I hardly answer the phone anymore.

I still have that rock.

It’s in the box

in the back of the car

with my cobra pin,

the one I carry for good luck

and for protection.

There was that other man, in Cortez,

begging money for a friend,

also with a face

that spoke of ancestry and alcoholism,

saying, “It’s cold out here tonight,

he’ll freeze to death.”

You were in the store buying ice cream.

I gave him three dollars.

I should have given him my blanket.

If you didn’t really want to die

they will hold you down

and

if you didn’t really want to die

they will not speak to you

only to each other

small talk with the syringe from one hand to another

like a shaker of salt

at a lunch table

that you won’t be sitting at

and in that moment

you die a little

even if

you didn’t really want to die

before

the door locks behind you

people come and go

you stay

and the light is thin through

thin windows

always the same behind glass

you don’t even have shoelaces

only socks

rubberized

so you don’t slip

and stumble

your way into line

“Take this,”

if you didn’t already

want to die

They don’t tell you what it does and so you stop asking.

You swallow the pills

because you have to

and you wonder,

dimly,

why you want to die now, when you didn’t really want to die before

when, really, you were

just trying to explain that it was hard to live

History is tricky.

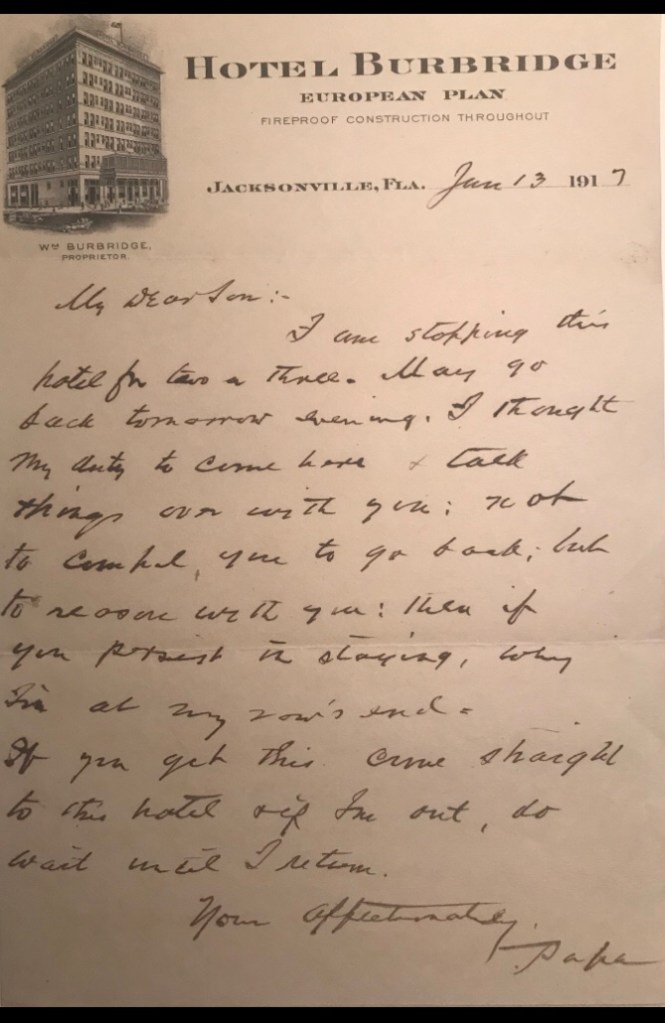

We have only the records of the past to construct our knowledge of what happened before our immediate witness. Even when the history explored is our very own – experienced and remembered – the truth is slippery.

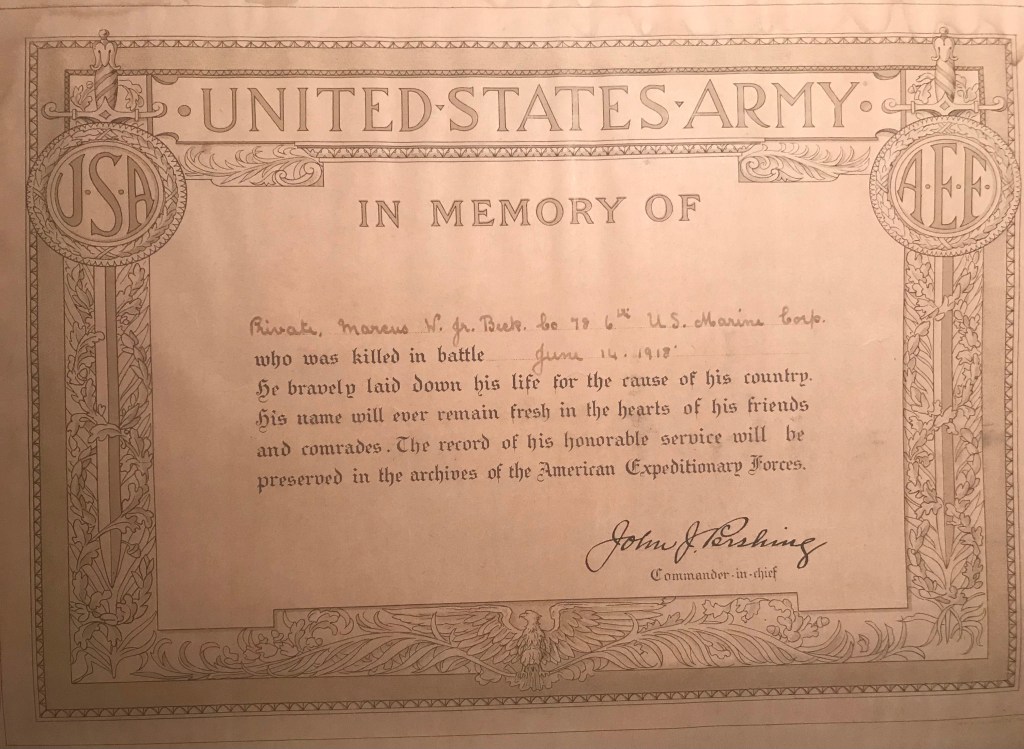

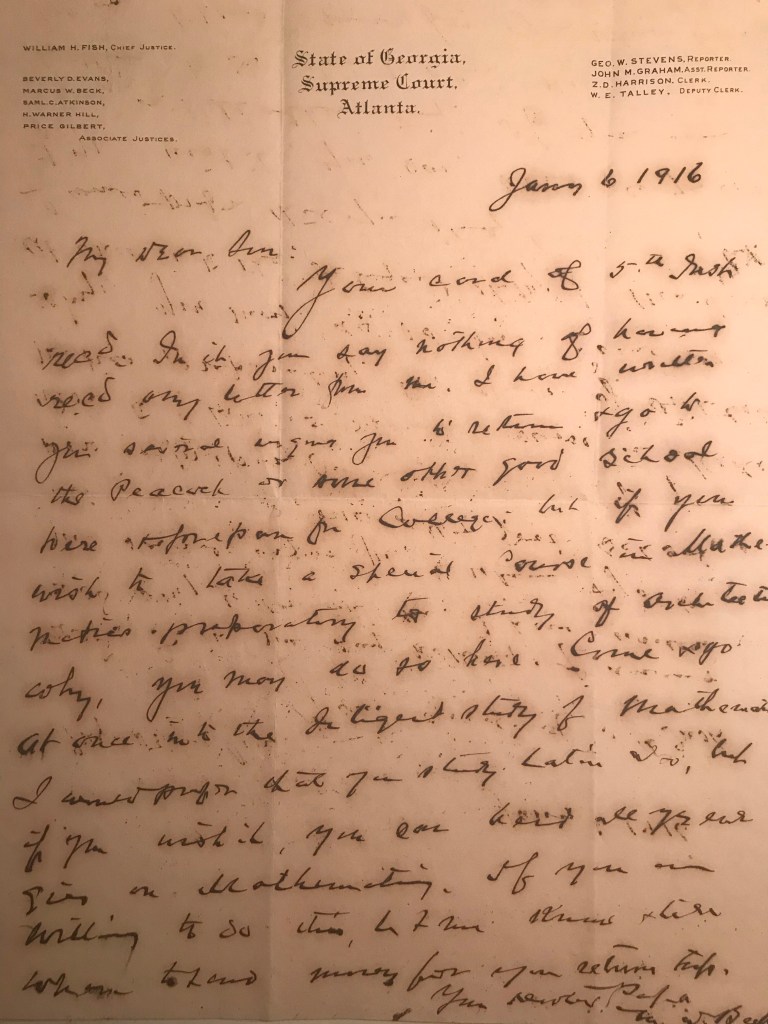

This is an incipient autoethnographic process, meaning that I’ve only recently begun to review, catalog, and transcribe the ‘papers’ stored at my parents’ house, which detail through saved letters and documents – a receipt for a train ticket, a certificate given for having died in the war – my great-great uncle’s running away from home at age 16 in 1917 and his subsequent experiences in the Marine Corps training prior to being deployed to fight in WW1. He died in mid-1918, just 18 months after he had written home from his run-away to Florida that he wanted to be an architect.

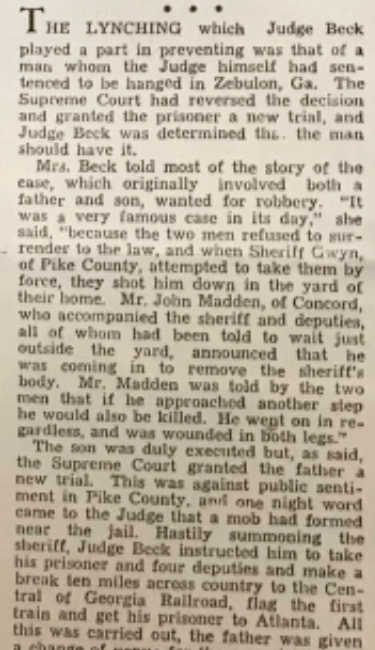

His father – my great-great grandfather was a presiding Georgia State Supreme Court judge during the same era that gave rise the 1906 race riots in Atlanta and the sociopolitical infrastructure that would give rise the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia, which Judge Beck was involved in, though only in ways both required of and appropriate for a Presiding Justice of the Georgia State Supreme Court in an ongoing post-Reconstruction era of ‘pressures from Washington’ to staunch and extinguish – once and for all – the smoldering bones of structural inequity and the flames of common hate in the American South. That said, it is likely that Judge Beck, while he may not have been out burning crosses in the yards of poor Black families, was almost certainly a person of power and influence in the development of formal organizations of hate in the State of Georgia. Additionally, one would imagine – at least I do imagine – that the cooperation of the head of the formal system of justice in the state would be necessary to facilitate many of the backroom wheelings and dealings – shall we call them? – protecting and funding organized domestic terrorism within the State of Georgia, as well as turning the blind eye to violent crimes committed against the sons and daughters of freed slaves in the American South, awaiting still the forty-acres and a mule promised to them as churches are set ablaze.

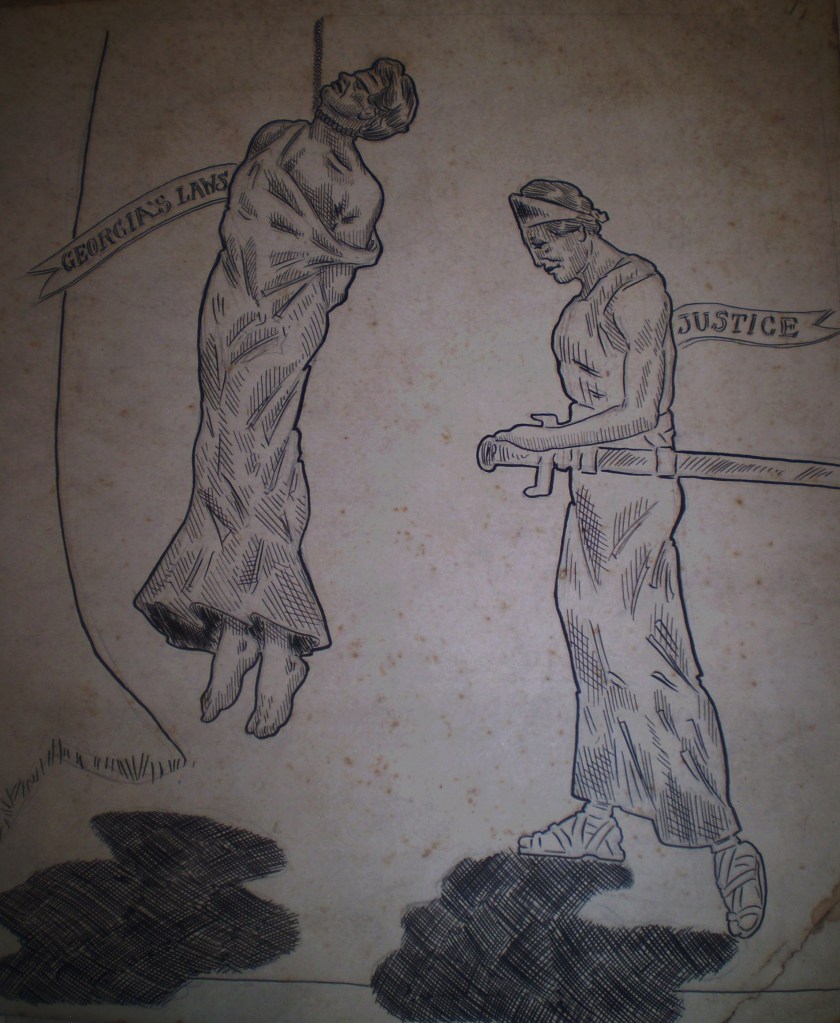

Marcus W. Beck, Jr. – son of the judge and my favorite dead uncle – was an artist and, as his pen+ink drawings suggest, opposed to prejudice and lynchings. He was a dark-eyed son, a prodigal son. Most bloodlines have a few of them scattered through the stories. Prodigal sons and rebel daughters.

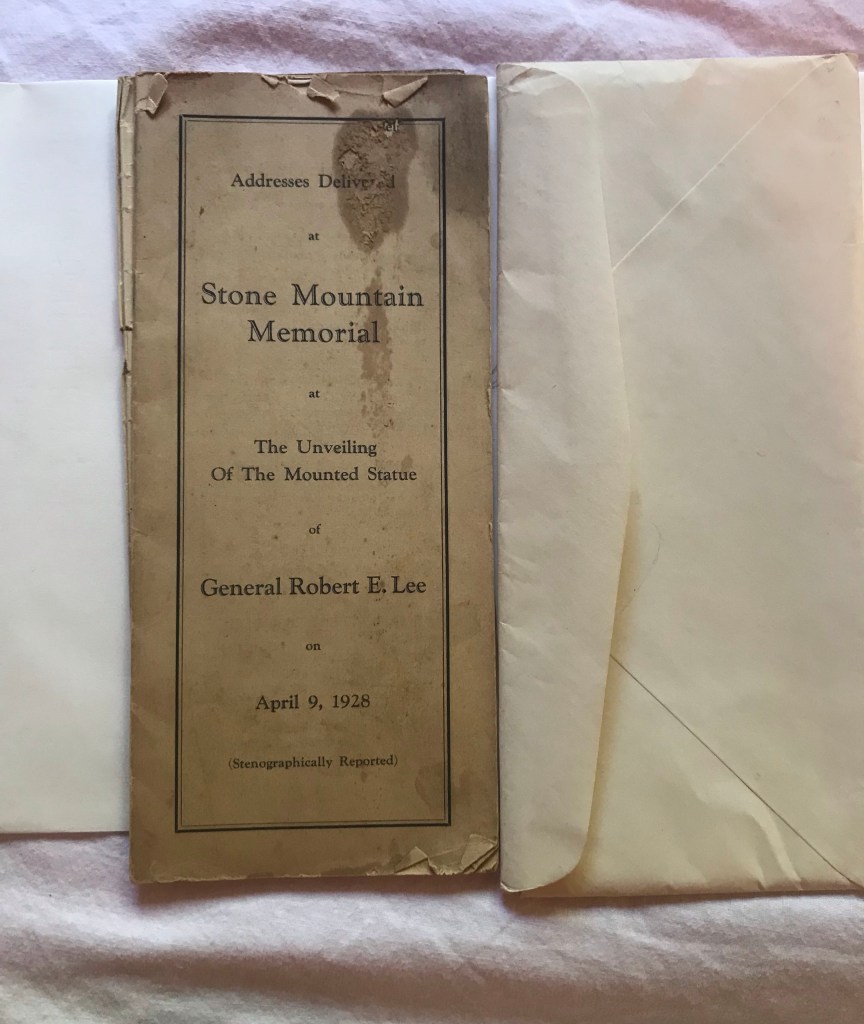

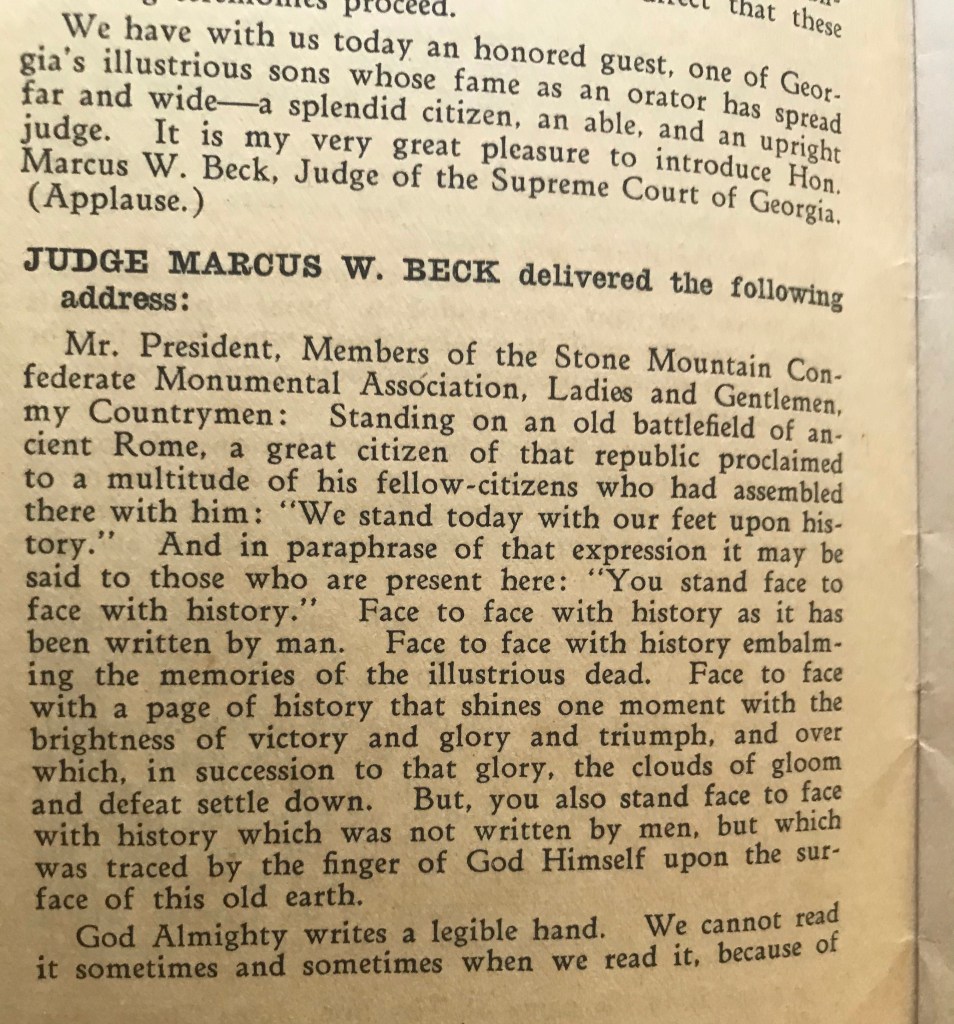

Ten years after his son died at the Battle of Belleau Wood in France, Judge Beck accepted the carving of Robert E. Lee at Stone Mountain, Georgia on behalf of the South.

As I consider this cache of family history from my father’s bloodline, I am reflecting on my experience of learning about this particular branch of my ancestry – my thoughts and feelings about this history I am discovering, my judgements and laments.

I am deeply considering why I may feel so conflicted, sick, and sad to think about the story of my great-great uncle Marcus who was an artist that wanted to be an architect and his father the Judge-with-a-dead-son going on and on in his long-winded acceptance of the Robert E. Lee monument while the crowd stood in an uncharacteristically cold April rain waiting for him to finish his long, bizarre speech.

I don’t know what it is about humans that make us so fascinated with what came before our brief little time, our nanosecond lives on earth.

Who am I?

Who are my people?

What happened to create the world that I understand to be real?

What are the stories that define who I am?

I grew up in the American South, and am – if I count back the sons and daughters correctly – a 6th or 7th generation Georgian on my father’s side.

It is worth noting that – in my opinion – nobody other than the descendants of indigenous people can justly claim multigenerational ancestry tied to any place in the lands we call North America, as their ancestral lineages stretch back thousands of years.

The rest of us Americans are the descendants of immigrants, refugees, or colonial conquerors.

Although my mother is from Florida, her grandparents immigrated to the United States from Lebanon in, I believe, the 1890s. They had intended to go to Albany, New York, but due to what is explained as ‘getting on the wrong train,’ they ended up in Albany, Georgia at the edge of the 20th century, just three decades after the end of the American Civil War.

Although the Nicholas (ex Khoury and al-Shahaidi) family eventually moved to Miami, they lived in Georgia at the same time my father’s great-grandfather was gaining judicial stature.

My maternal grandfather – brown eyes, brown skin, tightly curled black hair, a mother who spoke little English – was born in 1907 in Albany, Georgia, the year after the riots in Atlanta.

I know nothing of his childhood and very little about my mother’s Lebanese ancestors in general, who they were, where they were from, what their experiences as immigrants held.

As an adult, the man who would become my mother’s father married late to a young switchboard operator named Faith, who had come out of an abusive family line in Alabama. They had 3 daughters and lived on SW 23rd Terrace in Miami, a small house with Spanish tiles on the roof.

When their youngest daughter – my mother – was 10, my Lebanese grandfather dropped dead of a heart attack on a business trip to Jacksonville, the city I would be born in 16 years later.

He was an low-level executive in the Florida Milk Co. The few pictures of him are photos of him at work, black and white company photos.

In photos, he is the only brown man in the room, but he is smiling, and looks happy, a light in his eyes. He seems American in his suit and tie.

His family spoke Arabic until they learned English. My mother called her paternal grandmother sit’ti and in the 1980’s, I ate kibbeh, lebneh, and khubz arabi when we went to Miami. My mother made lentils and rice as frequently as she did spaghetti, prepared spinach pies with shreds of American orange cheese instead of lemon juice and vinegar.

I am the only one on my mother’s side of the family who has studied Arabic, who made an effort to learn the language of where some of my people are from, a language that was forgotten in the ever-present glare of necessity to speak English, to be American.

I imagine that people in Albany, Georgia at the turn of the 20th century might have…what? Disliked the Lebanese immigrants? Discriminated against them?

I don’t know. I can imagine all sorts of things, but I have no facts and – like I said – facts are dubious when it comes to history.

Judge Beck was appointed to the Georgia State Supreme Court by Governor Joseph M. Terrell in 1905, a year before the Atlanta race riots of 1906.

The term ‘race riots’ may not be an accurate descriptor for the events that took place in Atlanta the September that my great-grandmother was 11 and her brother – Marcus Beck, Jr. – was 8 or 9.

What happened in Atlanta in 1906 was a massacre, ‘a mass beating, a mass lynching. The term ‘race riot does not name the details and descriptors of what happened in Atlanta.

‘Race riot’ does not explain that a violent mob of 15,000 – 20,000 white men raged through the city destroying Black-owned businesses and gathering places, killing dozens of Black people in the streets. The official death toll was 25. Nobody knows how many Black people really died. Some estimates place the death count at over 100.

Only two white people died, and one was a white woman who had a heart attack after seeing the violence in the streets outside her home.

‘Race riot’ doesn’t name white supremacy, or white violence.

In my mind’s admittedly imperfect conceptualizations, a ‘race riot’ means that a large group of people from a marginalized and racially-oppressed demographic group take to the streets in an angry and unruly manner in outraged and grieving response to race-based injustices. Property may be damaged, such as the burning of police vehicles as a response to police brutality, and opportunistic looting may occur.

A ‘race riot’ does not mean a small army of demographically distinct people sweeping through a city, entering neighborhoods and killing people from another demographic group.

‘Race riot’ does not mean 15,000 white people – (Men and boys, mostly, I’m almost sure, as it was likely not proper for white women and girls to be out in the street committing acts of violence, though if one has ever seen the ugly hate on the faces of white school girls protesting school integration in the mid-20th century, 50 years after the Atlanta race riot, it is easy to imagine white women and girls cheering on the brutality committed by their male counterparts.) – publicly killing dozens of Black people and going out of their way to destroy Black-owned businesses, burning Black homes.

It was not until 2006 that the Atlanta race riots were even officially acknowledged by the state of Georgia.

I can recognize in myself a subtle sense of embarrassment, a sheepishness, in admitting that I had no idea that there was a ‘race riot’ in Atlanta when my great-grandmother was about to turn 12, when her Papa – as they called him – had just become a Supreme Court Judge the year before.

The Atlanta race riots of 1906 were not part of the Georgia History curriculum taught at Mary Lee Clark Middle, Camden County, c. 1988.

Although I have a minor in Black Studies with a BA in Sociology from Portland State University, I don’t remember any African-American History courses that mentioned the Atlanta race riots. This event probably was taught, perhaps in a lecture crammed full of the brutal beatings and racism-fueled fires of the early 20th century in the American South – but, I took those classes 25 years ago and – to be honest – a lot of history just blurs in my mind, the details and names and dates slurring into a cluttered timeline of mass atrocities that leaves my heart heavy with the enormity of how many ugly things happen in the world.

I wonder what it was like for them, the children of the house. Rachel and Marcus, their older sister Margaret. Their father was an important man, had become an important man. Their Papa was a judge. They were home with their mother, going to school. I don’t know what their lives were like, the day-to-day of home and childhood, their little world.

One Saturday afternoon, the newspapers reported that two White women had been raped by Black men and the city exploded into violence.

I wonder if my great-great grandfather went out into the mobs. He was, after all, an ‘important man.’ He may have only watched the violence.

Regardless of whether or not he was in the streets as a ‘rioter’ – it is very, very likely that he contributed to the violence – condoned it, perhaps even sanctioned it, agreed to allow it, conferred with the Sheriff and deputies who – it is said – openly participated in the public beatings and burnings of business.

As I write this, I notice a sick-ish feeling in the center of me and I don’t know – specifically – why I feel this.

Is it the knowledge that accusing a Black man of raping a white woman, or – in the case of Emmett Till, whistling at or even talking to a white woman – was (and in some places, in some minds, still is) essentially a warrant for violence against the accused Black man, as well as violence against people of African descent in general?

Is it the knowledge that my great-great grandfather was involved in the establishment of structural and systemic racism in the state I grew up in, those bloody ties between injustice and the justice system?

Just as the facts of history blur in my mind, my heart’s response (and my nervous system’s response, my mind’s response) to the rampant ugliness of American history, world history, the reality of slavery, old mothers mourning stolen sons in Sierra Leone) is less a specific facet of feeling and meaning, and more an overwhelming though quiet wash of feelings and images that sums itself in feeling sick, feeling sad, graven at the center of me.

My ability to articulate any sort of coherent incisive reflection or analysis is blunted and stammering, regressive almost, stammering like a child about how it’s just so grossly wrong, all of it.

“All of what, Faith?”

“All of it! People and society and stores and wars and this disgusting commodification of every fucking thing, rape culture, slave economies, police brutality. All of it.”

I feel like spitting. My hands are tingling with wanting to clench. I can feel something big and righteous in my chest, an aggression. An anger. I am an outraged child, tormented by the dissonance of knowing that people I love and who I want to see as good people do things that I know are deeply ugly, wrong, deplorable.

It’s interesting to think about the perspectives of the white men who took the streets in a killing mob one Saturday night. They were probably feeling righteous about themselves and what they intended to do. In the context of who they were and the times they lived in, they probably thought their actions were serving some twisted justice.

It strikes me, however, that perhaps they were also excited, that maybe they wanted to kill and destroy, that they seized the righteousness they found in the perception of themselves as the white male savior and protector of white women against a perceived threat, and allowed that male human bloodlust to be released en masse.

One thing I do remember from my African American History class is my professor asking us if we thought that any Black man in his right mind would dare to sexually assault a white woman with so many examples having been shown to him of what happens to Black men if they mess with white women.

White men had raped women and girls of African descent for generations and generations, had brutalized women and girls of African descent.

God, I feel sick.

7/06/2013

Everyday, this time of year especially, I think about my favorite dead uncle.

It has been about 3 years since I opened up the box of papers and set his ghost free.

How do I know there was a ghost?

I could feel it.

I don’t know why I decided to ask my father about Uncle Marcus’ letters, where they were. It’s possible that I simply remembered they existed, and wondered what had happened to them.

I was surprised to find out that the box of letters and photos was here, in the mountains.

Then again, where else would it be?

I think I wanted to see his drawings, because I was drawing a lot then – a picture every day for a year, already well into the 3rd quarter of that project and learning how to forget to try, to forget my own ideas, to let the pictures be what they wanted to be. I had started to see and to notice the shapes in everything, and remembered sitting on the wooden front steps of the house I grew up in, the Dome House – which is what my parents took to calling the stilted plexiglass and lumber icosidodecahedron and long kitchen hall with bedrooms and decks and stairways down to the grey sandy yard shaded by oaks that dropped dead leaves all year long, littered the ground with their beetle-brown shells, the Dome House on the river bend, if you break west from Borrell Creek and travel the map of the lands edge, past the point where the cedars grew and the sand was clean, smooth, almost a beach, that place once it ceased to be the place they called home – listening to my father tell me that clumps of bubbles fuse in 60 degree angles, making hexagons…endlessly and without will.

In the period of time that my adult-world marriage had thoroughly crumbled, and I had been drawing everyday, I had started to remember many of the things that I had not remembered for a very long time, and – to be honest – it was a bit much, the remembering…all the remembering.

I opened the box very innocently, just wanting to look at old things and think for a few minutes about the smell of my great-grandmother’s house and about the closet that the papers were in, the closet in the room on the shady side of the house, with hydrangea an impossible blue beneath the second story window of the room with the cabbage rose wall paper.

The closet seemed to gasp out all its dusty, old smells in surprise when the light – a bare bulb on a brittle string – was turned on with a decisively incandescent click to display in swinging shadows shelves of boxes and old rows of shoes, a war helmet on the wall with the words “War Is Hell” written across the top of the old canvas.

We knew that there were letters in the boxes, though we never saw them. The boxes were never opened. We knew the letters had something to do with Uncle Marcus, who died before ever becoming an uncle.

We know this because his sister, my great-grandmother, told us. She was the one who saved them, all that proof of the brother that she had lost.great-grandmother saved them, all that proof of the beloved brother that she had lost.

They say that he was “special, an artist.”

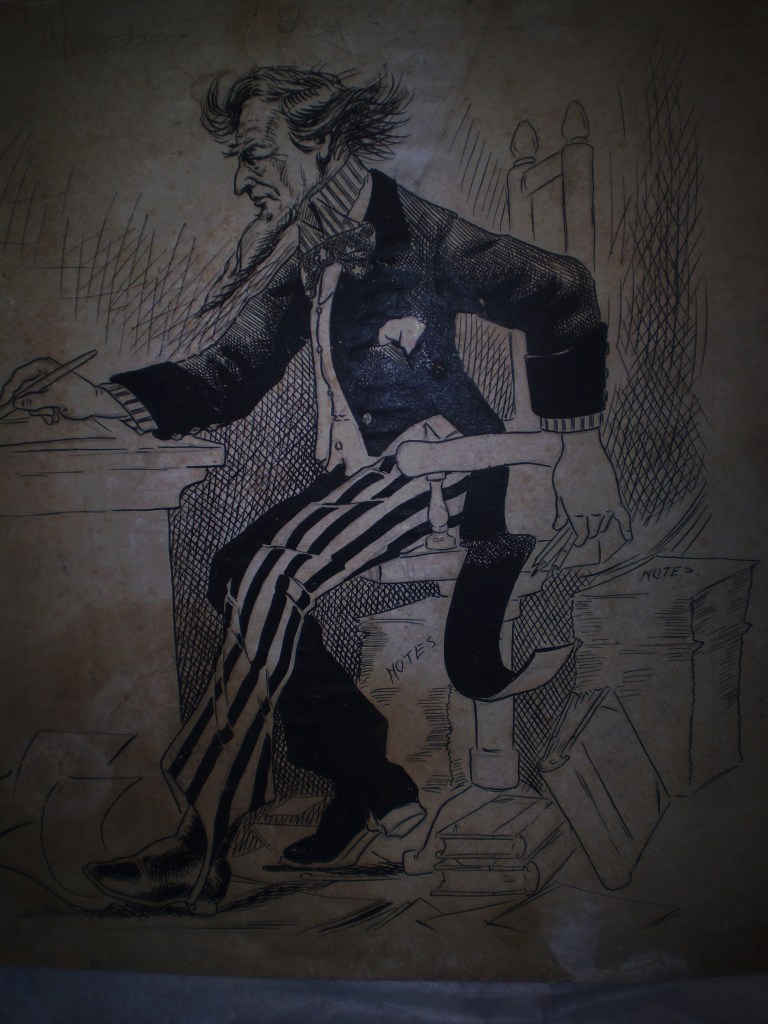

I was in my mid-30s when I first saw Marcus’ drawings, and understood that he was deeply critical of politics and laws…and lynchings.

As a teenager, he drew the picture above, which depicts a sword-wielding figure with a sash reading ‘JUSTICE’ hanging a classical white woman-ish figure with a sash reading ‘GEORGIA STATE LAWS.’

He was the son of a Georgia judge in the early 20th century.

When I was young, and wanting to draw pictures, people would remember him. I don’t think I ever identified with him though, except to wish that I might be special, too and to long to have enough bravery to run away to the circus, or somewhere.

My family – like most families, I guess – is full of histories that nobody ever talks about.

We did not speak of the way my father’s mother briefly married her professor, or how it was that the professor came to leave just after my father was born, the marriage annulled. For years, I did not know my paternal grandfather’s last name. I still don’t know his first name, and have never had any contact with any of the people I am related to through his bloodline.

We did not speak of how my great-grandfather died or the fact that my beloved great-grandmother was an alcoholic.

Why have I never wanted to write a book about my great grandmother?

She was the one who taught me to play cards, after all. She was the one who taught me to tell stories.

Why has her ghost never clamored at me the way her brother’s has, nagging “Tell my story, tell my story…”

Perhaps it is her, not him, that is nagging?

Maybe it is both, doing as children do, which is to try to get what they want, to get what they need, to have their voices heard.

Why else would she have saved his papers and drawings?

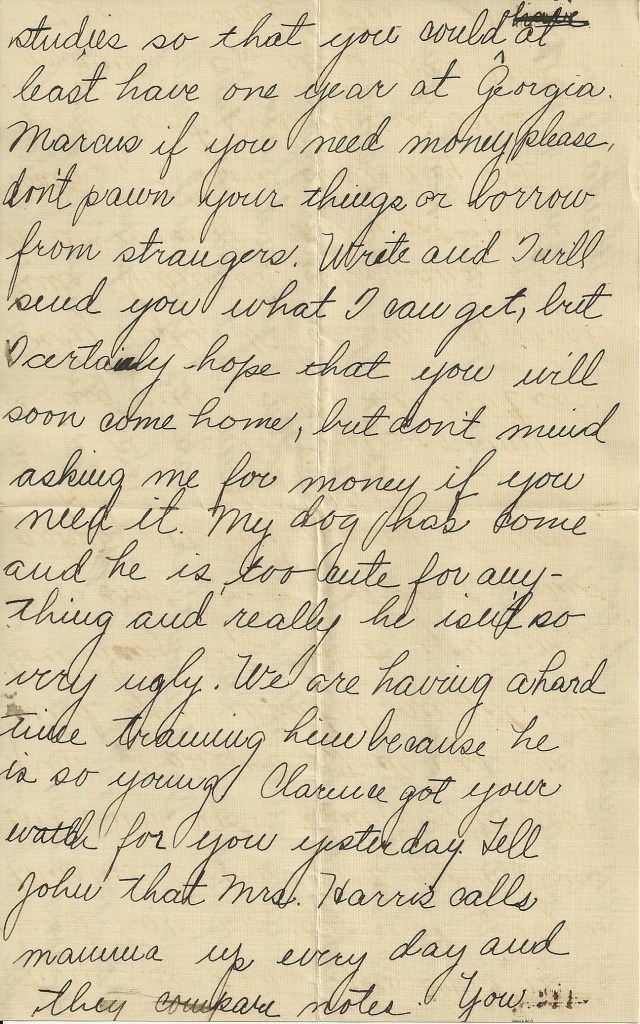

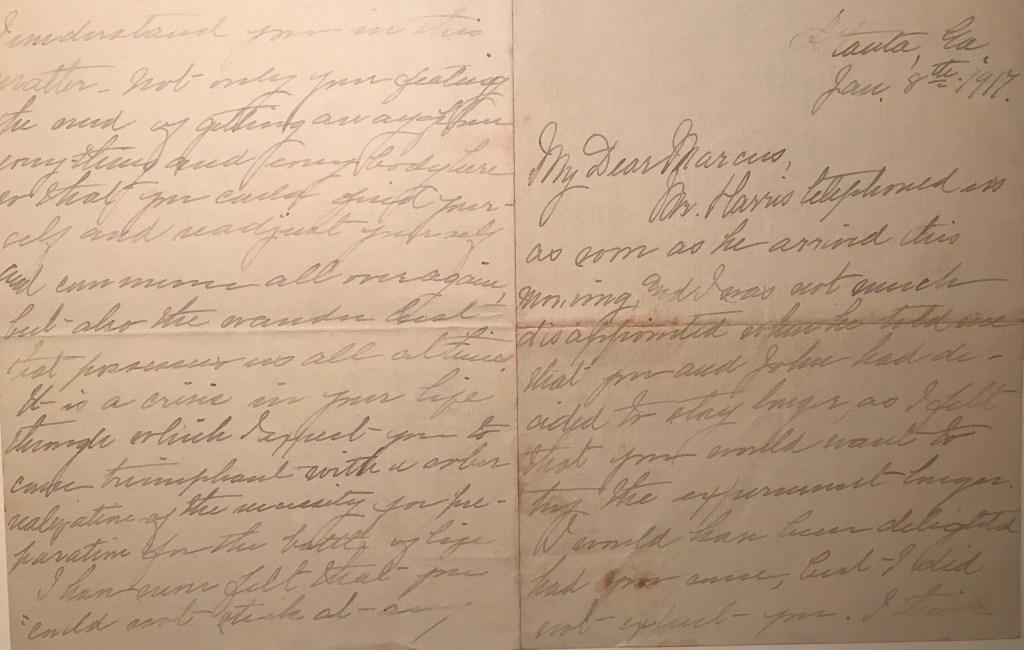

A Letter From Rachel Beck Moeckel to her Brother Marcus, Jr. (1917)

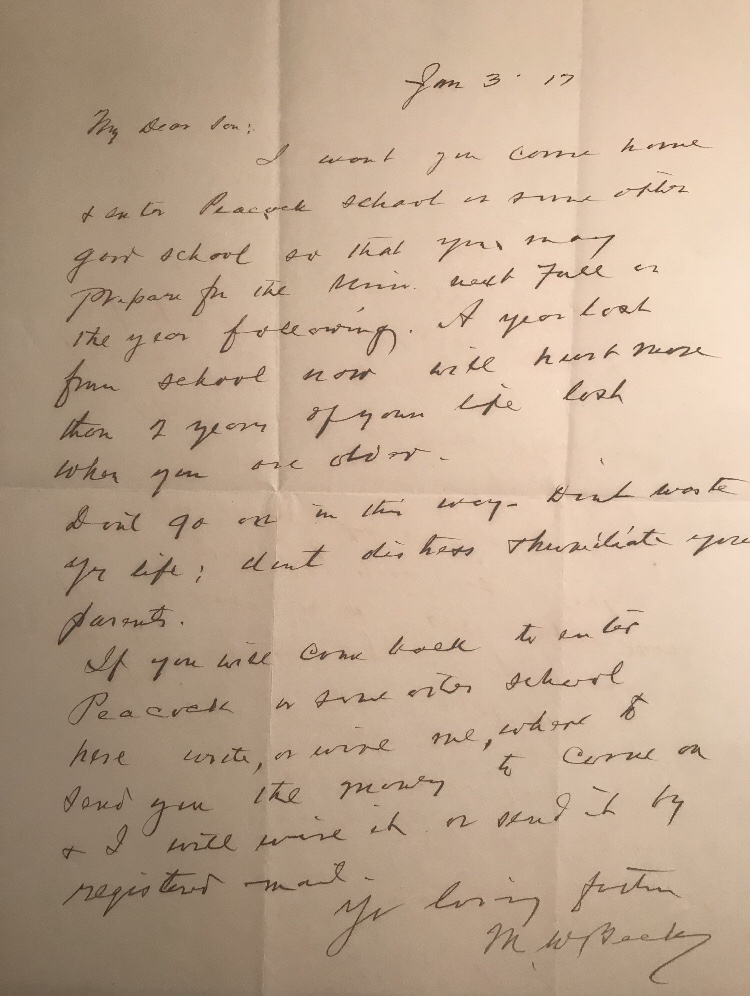

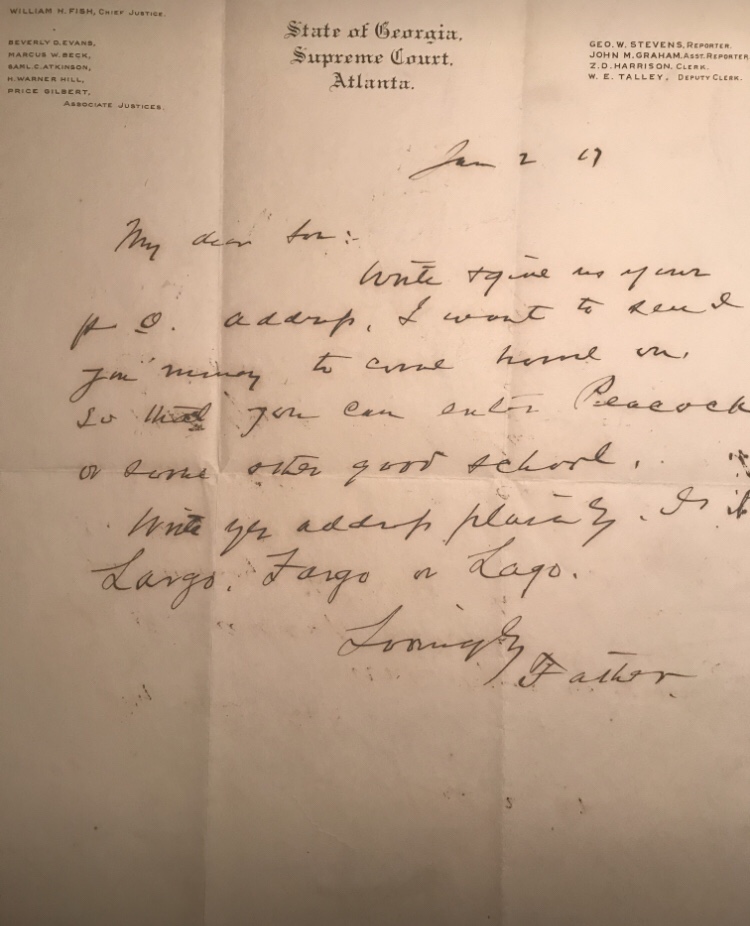

Jan 3, 1917

My Dear Son:

I want you to come home and enter Peacock School or some other good school so that you may prepare for [?] next Fall or the year following. A year lost for school now will hurt more than a year of life lost when you are older. Don’t go on in this way; Don’t waste your life. Don’t distress and humiliate your parents. If you will come back to enter Peacock or some other school here write, or wire me, where to send you the money to come on & I will wire it or send it by registered mail.

Yr loving father,

M.W. Beck

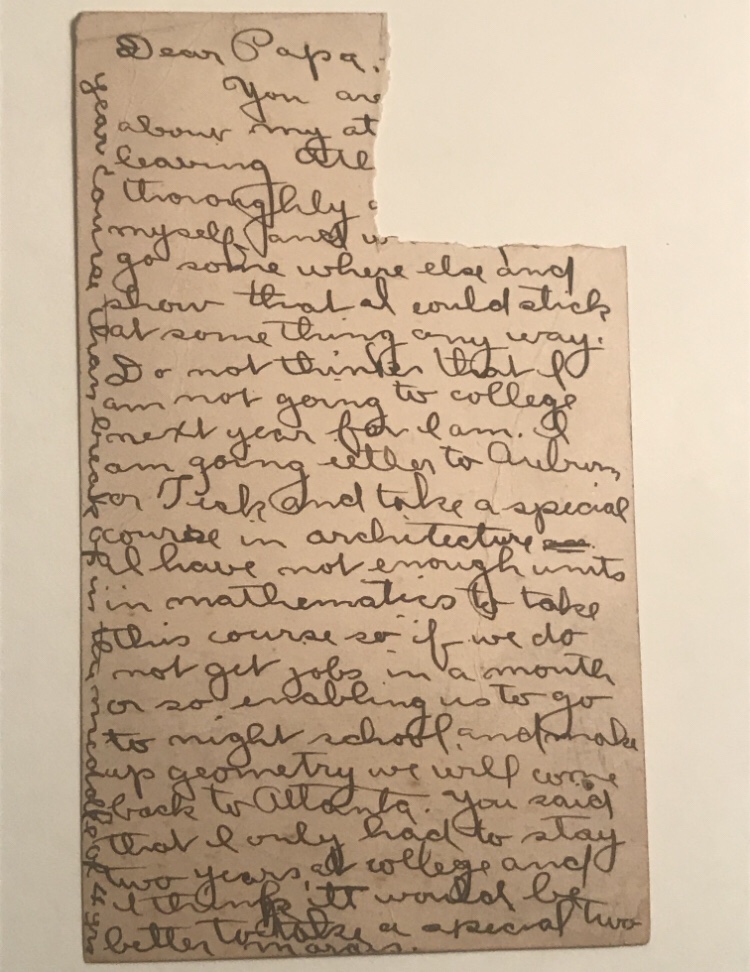

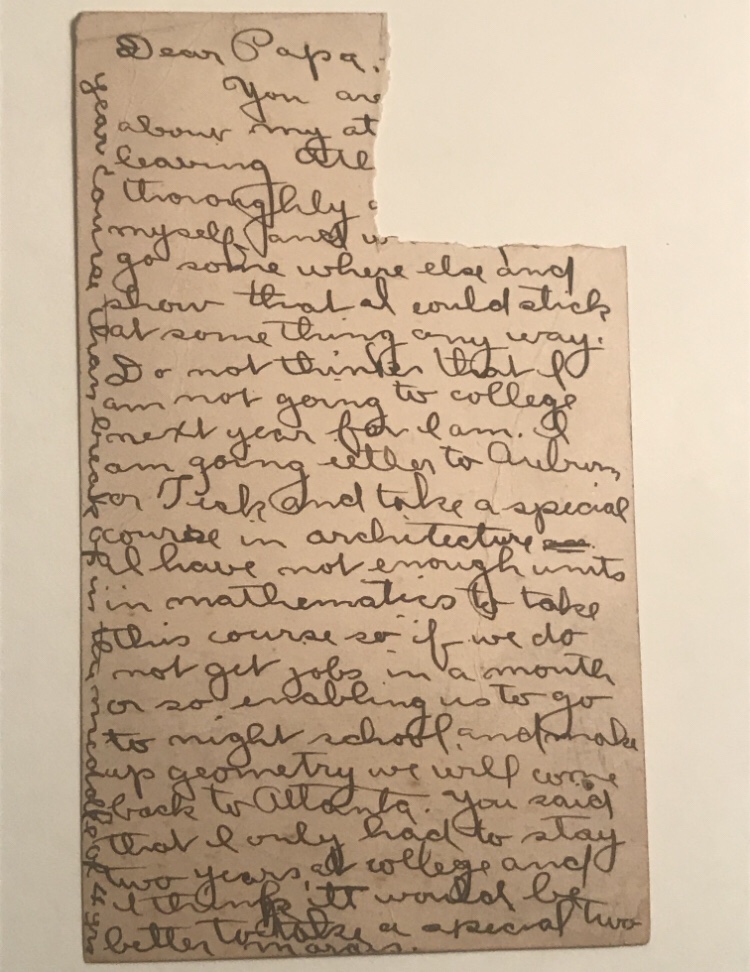

Dear Papa,

You are –

about my at –

leaving [?] –

thoroughly –

myself and –

go somewhere else and show that I could stick with something any way. Do not think that I am not going to college next year for I am. I am going either to Auburn or Fisk and take a special course in architecture. I have not enough units in mathematics so if we do not get jobs in a month or so, enabling us to go to night school and make up geometry we will come back to Atlanta. You said that I only had to stay two years at college and I think it would be better to take a special two year course than break off in the middle of 4 years. Marcus

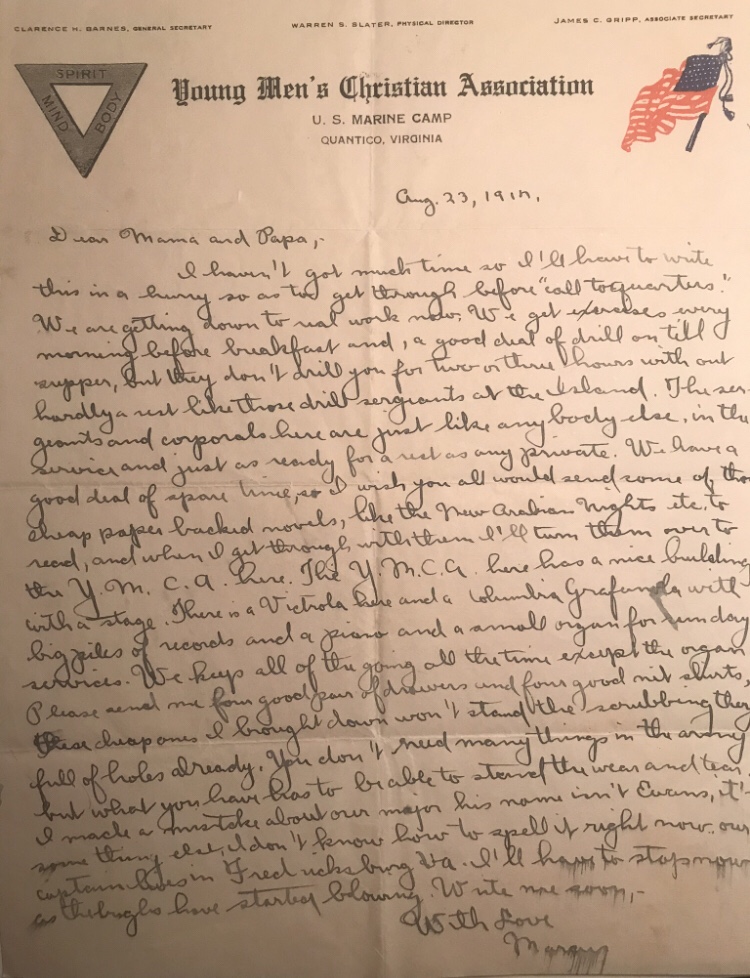

Parris Island, S.C.

July 4, 1917

Wednesday

Dear Mama and Papa,

I am writing you this way because I am afraid if I write two letters that I won’t be able to finish both of them. Today’s the big day here and instead of celebrating with noise and powder, we’re celebrating with athletic meets. We get enough fireworks on the rifle range on other days. We haven’t started shooting yet. We are just snapping in. Snapping in is when you learn how to aim and hold the gun, judge distances, etc. it’s the hardest and most important part of the range training. “Colors” just blew, sixteen bugles all blowing together and everybody standing at attention.

[stamp reading M.W. Beck, w/ text reading “This is the way we mark our clothes”]

There is going to be a big fight tonight to decide championships of the island. It’s between a fellow in training and an old timer named Kelly, who is the present champion. The new man is an amateur from N. Orleans. I broke my resolutions and bet $5 of my next months pay into the New Orleans fellow. He’s in the next street to us. Nearly everybody in camp has bet up on this fight. I don’t consider it the same as playing poker for money or shooting craps. We had some dinner today. Real chicken, (unreadable) potatoes, an orange and a banana apiece and all the lemonade we could drink. X That cross represents a pause. The (unreadable) down at the docks fired the first salute and everybody ran out in the rain to watch it. There were fifteen salutes fired. The light’s so poor I have to

[end of page]

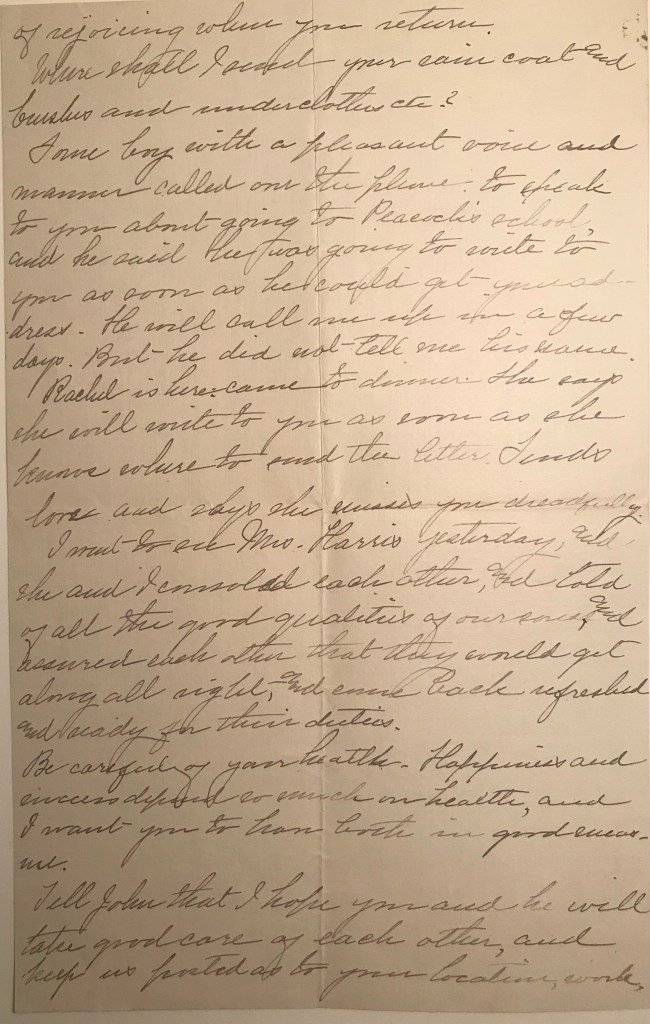

I just got home from Fairview, where my father – as he folds old shirts he calls Hawaiian, but that are really more Floridian, with dolphins and colonial compasses and sportfishing boats – tells me again that I should just get in touch with the people at the University of Georgia and tell them that we have all these old family papers, original documents from the life and career of Marcus W. Beck, whose journals are archived at the university and who is of historical significance due to him being a Georgia State Supreme Court Judge during the first quarter of the 20th century, as WWI unfolded, raged, and took the life of his namesake son following a year of tense rebellion that produced a thick sheath of correspondence between young runaway Marcus, his father and mother, and his sister Rachel, who was my great-grandmother and who I was raised with until her death when I was 16, in 1992. Rachel kept the letters and papers in a closet upstairs in an unused room on the northwest side of the house, perched above the bright blue hydrangea that bloomed and nodded heavily in the shade alongside a dirt road that I still dream about frequently.

Rachel Beck was born in 1894, and so I grew up in the 1980s in South Georgia just down the road from a person I loved that was born in another century.

Marcus W. Beck was significant not for groundbreaking legal decisions that changed legislature, or for his authorship of seminal works of law, ethics, or literature, which – to my knowledge – he was involved in neither, but because in April of 1928 – on behalf of the South – he accepted the as-yet-unfinished monument to Robert E. Lee at Stone Mountain, Georgia, a monument that over the next 40 years would become the largest confederate monument in the United States.

Judge Beck accepted the monument on behalf of the South via a speech that my father tells me that ‘some article somewhere’ reported was a lengthy speech on an unseasonably cold and wet day in early April, 1928.